Teaching Less, Learning More

Whether you’re leading a workshop, teaching a class, or simply trying to help people engage more meaningfully, this question strikes at the heart of what it means to facilitate learning. And the answer often begins with a radical act: stepping aside.

The other day, while rummaging through my collection of articles about group work, I stumbled on two gems—both from 2015—that exemplify this idea beautifully. They’re powerful reminders that sometimes the best thing we can do is…less.

The Silent Professor

Hat tip to Alfie Kohn for pointing me to this first one, written by Joseph Finckel, a professor in the English department at Asnuntuck Community College. He writes:

‘I teach English, and midway through the spring 2013 semester, I lost my voice. Rather than cancelling my classes, I taught all my courses, from developmental English to Shakespeare, without saying a word. Though my voice had mostly returned by Tuesday evening, what I was observing compelled me to remain silent for the remainder of the week. My experience teaching without talking proved so beneficial to my students, so personally and professionally centering, and so impactful in terms of the intentionality of my classroom behavior that I now “lose my voice” at least once every semester…

…Teaching without talking forces students to take ownership of their own learning and shifts the burden of silence from teacher to student. It also forces us to more deliberately plan our classes, because we relinquish our ability to rely on our knowledge and experience in the moment.

At the end of a class during which I did not speak, a student remarked that it had been the best discussion she had yet had. Take the pressure off of yourself to teach, and instead create a situation in which learning will occur. If that means remaining silent, don’t worry—you will not have lost your voice.’

—Joseph Finckel, The Silent Professor

As someone who spent ten years teaching college and four decades facilitating groups, I still catch myself talking too much. It’s a deep-seated habit—and a hard one to break. But Finckel’s approach is a powerful reminder: silence can be one of the most generous and transformative gifts we offer learners.

His advice, “Take the pressure off of yourself to teach, and instead create a situation in which learning will occur,” deserves a place on every teacher’s wall.

The Magic of the Raised Hand

This next example comes from Chris Corrigan, a gifted facilitator, teacher, and steward of the Art of Hosting. It’s elegant, simple, and radical:

‘In the second before you let people get to work you ask the group a question: “Put your hand up if you have enough clarity from the instruction I just gave to get down to work.” Many, many hands should go up. Invite people to keep their hands up, and then utter these magic words.

“If any of you have questions about the process, ask these people.” And then remove yourself from the situation.

This does two things. First it immediately makes visible how many people are ready to get going and that shows everyone that any further delay is just getting in the way of work. And second, it helps people who are confused to see that there are people all around them that can help them out. And that is the simplest way to make a group’s capacity visible and active.’

—Chris Corrigan, The simplest facilitation tip to build group capacity

It’s a move that turns the group into its own resource. A small moment of informational hand-raising that changes the whole dynamic.

Learning Happens When We Let Go

These two stories show how learning can thrive when we consciously let go. Read the full posts to see how these subtle interventions move the work away from the teacher or facilitator and toward the learners. When we remove ourselves—by staying silent, or by redirecting questions to peers—we create the space for others to step in, step up, and own the experience.

So the next time you’re preparing to teach, facilitate, or lead, ask yourself: What might happen if I simply stepped aside?

Chances are, something extraordinary.

While facilitating, I try to remember that we are all different. Here’s why that goal can make me a better facilitator.

While facilitating, I try to remember that we are all different. Here’s why that goal can make me a better facilitator.

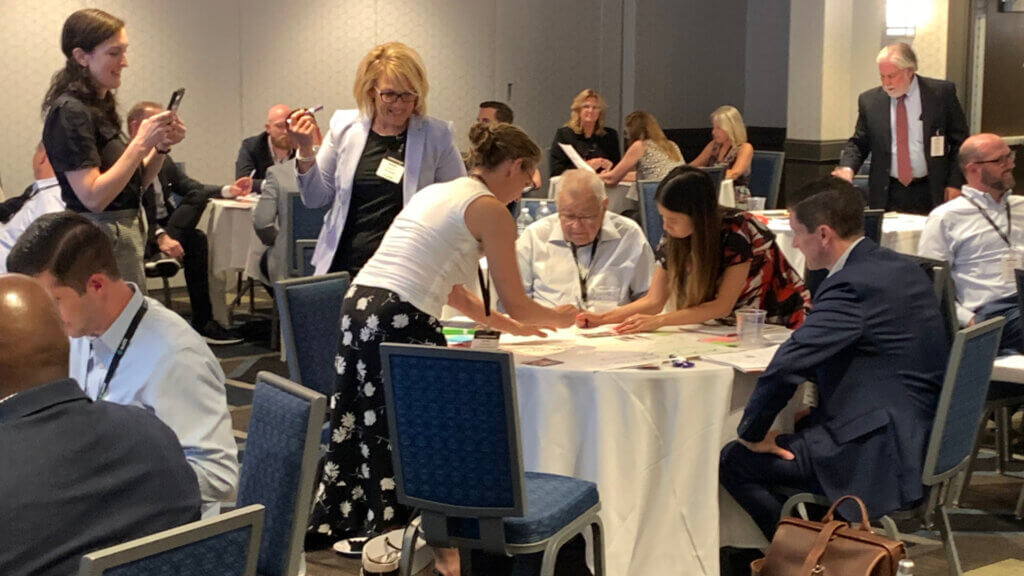

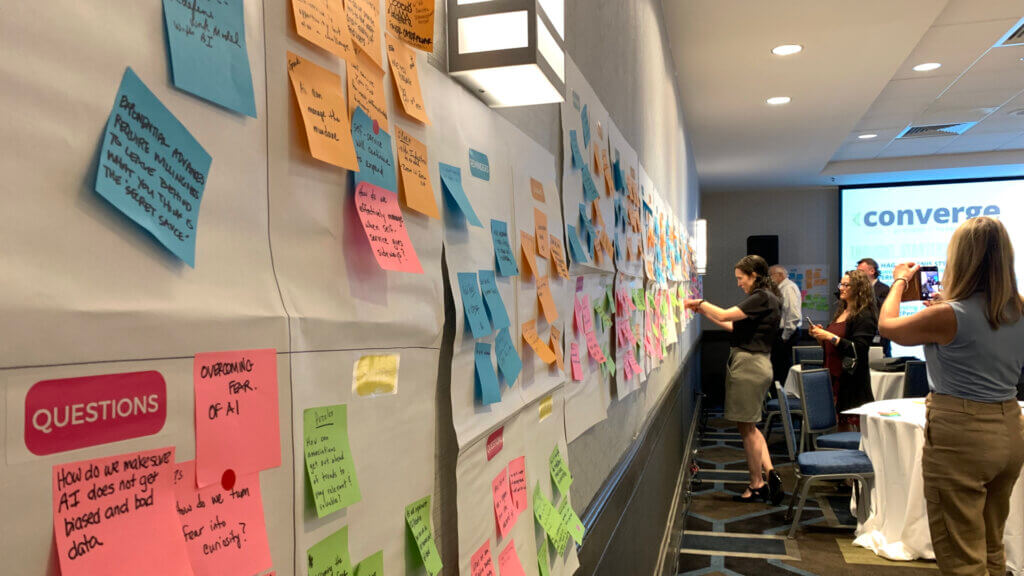

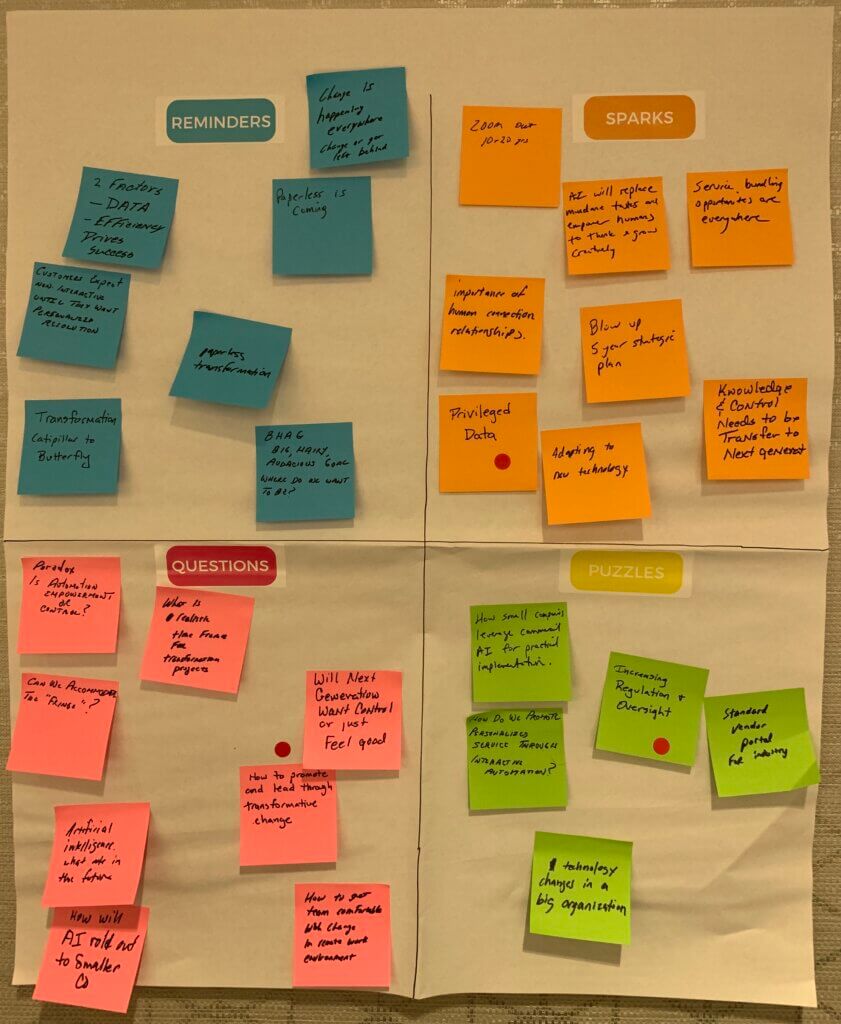

A June 2023 conference gave me a perfect opportunity to use one of my facilitation tools: Reminders, Sparks, Questions, Puzzles (RSQP). RSQP can be thought of as a highly interactive debrief after an information dump. It’s an efficient way to get participants to rapidly engage with and explore presented content in a personally meaningful way. And, as we’ll see, RSQP offers the potential to devise on-the-fly sessions that meet participants’ uncovered wants and needs.

A June 2023 conference gave me a perfect opportunity to use one of my facilitation tools: Reminders, Sparks, Questions, Puzzles (RSQP). RSQP can be thought of as a highly interactive debrief after an information dump. It’s an efficient way to get participants to rapidly engage with and explore presented content in a personally meaningful way. And, as we’ll see, RSQP offers the potential to devise on-the-fly sessions that meet participants’ uncovered wants and needs. To make our 2½ hours of participant-driven session determination a little easier, I combined RSQP with another facilitation technique:

To make our 2½ hours of participant-driven session determination a little easier, I combined RSQP with another facilitation technique:

I’m a big fan of the core facilitation technique

I’m a big fan of the core facilitation technique

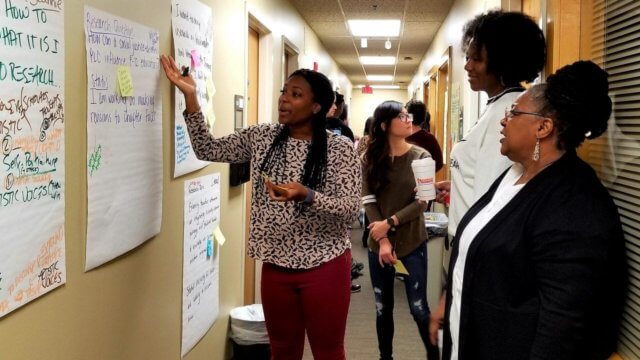

In a typical in-person conference breakout session, participants divide into small groups to discuss one or more topics. Each group records members’ thoughts and ideas on one or more sheets of flipchart paper. At the end of the discussions, groups post their papers on a wall and everyone walks around reading the different ideas. Facilitators call this a gallery walk. Here’s a tip to improve breakout gallery walks.

In a typical in-person conference breakout session, participants divide into small groups to discuss one or more topics. Each group records members’ thoughts and ideas on one or more sheets of flipchart paper. At the end of the discussions, groups post their papers on a wall and everyone walks around reading the different ideas. Facilitators call this a gallery walk. Here’s a tip to improve breakout gallery walks. I’m a big proponent of

I’m a big proponent of