I make a sales visit

In one of my former lives (the one when I ran a solar manufacturing company) I sold devices called air-to-air heat exchangers. These nifty units provide fresh air ventilation to buildings while simultaneously using the outgoing stale air to heat or cool the incoming fresh air, thus saving heating energy in the winter and cooling energy in the summer.

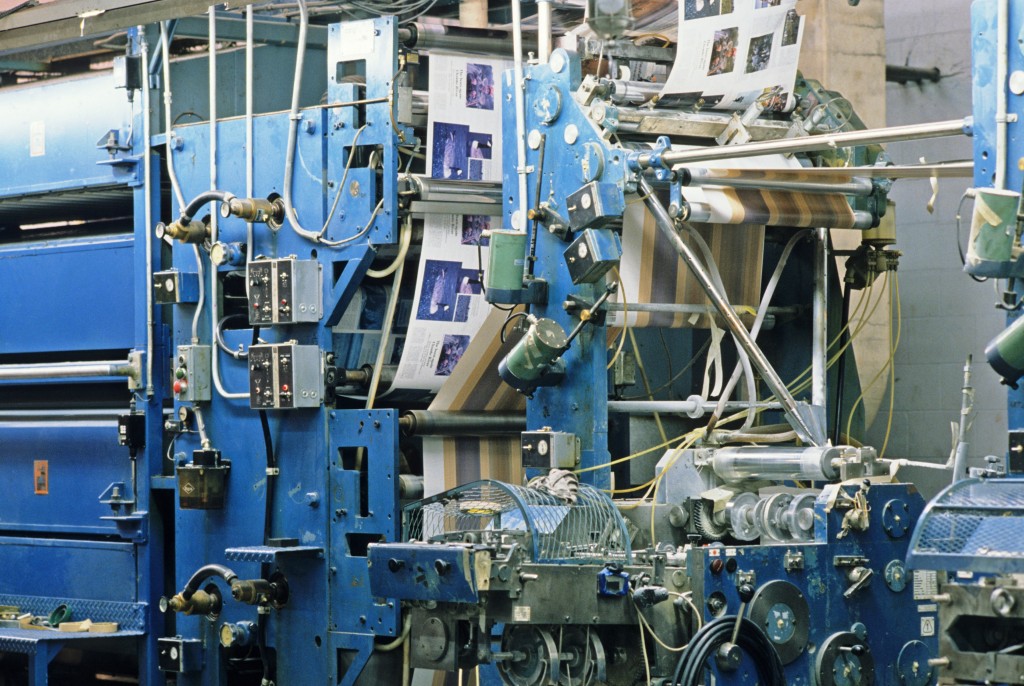

One day I met with the owner of a large offset printing shop who was curious about these gizmos. Entering the print room, the smell of ink almost knocked me over. As Bill showed me around I began to get a splitting headache. Confident that his business could use what I was selling I asked him how he put up with the smell.

“The smell?” he said. “Oh, I don’t even notice it.”

“Does anyone complain?” I asked.

Bill thought for a moment.

“Well,” he said, “I guess most customers mention it when they visit the plant. New employees too.”

He paused.

“But you get used to it.”

To me, desperate to flee the premises, it was incredible that anyone could adapt to the stink. And yet it was clear that everyone else in the building seemed to be happily going about their business.

Habituation

Bill and his employees were providing me, for better or worse, with a good example of sensory habituation. Sensory habituation involves our amazing ability to adapt to sensory stimulation to the point when we no longer notice it. The tick of the wall clock in your home, the lumpy mattress you sleep on every night, the flicker of the fluorescent lighting over your desk. You notice them at first, but in time they disappear from your consciousness. Your amazing neuroplastic brain filters out constant stimuli over time so we can concentrate on the new and unfamiliar.

Most of the time, habituation is a big plus. Imagine always being unable to concentrate on a conversation because of a loud clock ticking, being unable to sleep on your uncomfortable mattress, or getting a headache from the flickering lights in your office. But when we’re trying to change behavior, habituation can get in the way.

Habituation’s downside

As a child in school, most of the time teachers are teaching us things we don’t know. This is because we cram the fruits of thousands of years of human learning into ten to twenty years of school. There’s no way we can be an equal contributor to the teacher’s learning under these circumstances. As a result, is it any wonder that we believe that learning is something that only happens one way: from a teacher to a learner?

And while we’re being taught in school, we sit in straight rows of chairs so other kids won’t distract us while all this knowledge is shared with us. Is it any wonder that we’re habituated to believe that sitting in straight rows of chairs is how we should sit when we’re learning new things?

By the time we become adults, models such as learning and the “normal” room set while learning are habituations. Even though we know that working adults can quickly amass expertise and experience in their professional field that is of great value to their peers. Even though we know that straight-row theatre seating is perhaps the worst arrangement for facilitating the peer-to-peer interactions that are most effective at creating appropriate, accurate, and lasting learning.

Get unstuck

So how do we overcome our habituation to the familiar that may be preventing us from seeing something important?

When we are oblivious to our habituations, we don’t even notice things that might be worth examining. The first step is noticing.

We return from a vacation and, entering our office that has been absent from our life for a week we see the flickering light above our desk. That’s the moment when we have a chance to realize that something may be worth changing in our work environment.

We notice that our neck and lower back are hurting after 15 minutes while sitting at the end of a row twisted towards a speaker who is going to be talking at us for another 45 minutes. That’s another moment when we might make a note to revise the seating plan at our next event.

Amy asks us about a session two days later, and we notice we couldn’t remember anything the speaker said. That’s an opportunity for us to evaluate the effectiveness of the education we’ve been serving up at our conferences.

Noticing is tough. It’s easy to dismiss that little flicker of awareness and let the powerful force of habituation sweep us back into the familiar. A few hours later, we’ve forgotten that we even noticed the flickering light, and we dismiss our evening headache as an unwelcome side effect of going back to work.

That’s why the second step in getting unstuck from the downside of habituation is capturing what you notice. I’ve written about David Allen’s Getting Things Done, which explains how to create safe places to capture ideas and tasks. You can expand his methodology to capture things you notice too. Once captured, we can review them regularly to reinforce what we’ve noticed and begin to work on the process of change.

You can’t win ’em all

My visit gave Bill a chance to notice that his work environment was making newcomers uncomfortable. But the force of habituation won out. By the end of our time together, he remained unconvinced of the need for ventilation, based on his own and his employees’ habituation.

I didn’t make the sale.

The next time you notice that little attention flicker of something out of the ordinary, try capturing it immediately and reviewing it later. You may have noticed something formerly buried by your habituation, something worth changing.