A class is a meeting

Though I don’t teach college anymore, I’m interested in educational class design because a class is a meeting. And much of what we can do to design great meetings is applicable to college classes too.

So I had high hopes for a September 7, 2022, City University of New York webinar introducing Cathy Davidson and Christina Katopodis’s book The New College Classroom, which is “about inspiring, effective, and inclusive teaching at the college level.”

Sadly, I was disappointed. Not so much by the information presented but more by the way it was done. Talking about incorporating active learning, interaction, and participation into college classes is great. But talking does little to change the behavior of those listening. The speakers didn’t model what they were preaching during their talk!

The webinar platform and opening

The two-hour webinar was hosted on Zoom. It used a hybrid format with about 100 people present in person and 800 online. Chat was disabled, so online attendees could only interact via Zoom’s Q&A function. The presenters used Mentimeter for (two, I think) online polls.

Two hours of 900 people’s time adds up to 1,800 person-hours allotted to this webinar. Here’s a summary of my observations, plus suggestions on how the organizers could have improved the experience.

The webinar started 6 minutes late

Starting late is disrespectful and provides a poor model for what the “new college classroom” should be like. 90 attendee hours wasted! The meeting stakeholders could have done two small things to make it far more likely that the webinar would start on time:

1. Include two times in the meeting invitation. The time when the meeting will open, and the time when the meeting will start.

For example: “We’ll open the room and the Zoom meeting at 14:45 EDT, and start promptly at 15:00 EDT.”

2. To improve the meeting start experience further, let people know what (if anything) will be happening between the open and start time of the meeting.

For example: “Arrive a little early, and chat with our presenters before the meeting starts!”

See this article for more information about starting meetings on time.

Aaagh: The webinar began with 25 minutes of broadcast information!

First up was the Executive Director of the Futures Initiative, who thanked the sponsors and introduced the Chancellor and Provost of CUNY. She didn’t take too long, but the Chancellor and Provost were a different story. In total, attendees sat through twenty-five minutes of thank-yous, congratulations, and enthusiasm about the book and presenters that added nothing of value to the webinar. During this segment, I tweeted:

Watching the #newcollegeclassroom webinar. Over twenty minutes have been spent on this two-hour session, and we’re still on the introductions! With 800 attendees, that’s 300 person-hours wasted so far. I hope this is not representative of A New College Classroom.

— Adrian Segar (@ASegar) September 7, 2022

And a little later:

Quote from the current speaker in the #newcollegeclassroom:

“a frame you hear in lots of non-academic circles something like nothing changes in academia.

People outside of the academic world think we are stuck in old methodologies”Sadly, this webinar is validating that frame.

— Adrian Segar (@ASegar) September 7, 2022

The irony of the current #newcollegeclassroom webinar speaker describing the importance of participation in the classroom where no participation has occurred for 30 minutes.

— Adrian Segar (@ASegar) September 7, 2022

Introductions and thanks can be shared effectively in a few sentences. If attendees want to know more, they can easily find it on the web. The entire introduction could have easily been covered in five minutes at the most.

At this point, a quarter of the allocated webinar time had passed, and the presenters hadn’t even appeared yet! 450 attendee hours wasted.

Finally, the presenters appeared!

Finally, the presenters of the #newcollegeclassroom webinar appear after 25% of the webinar is over. It sounds like there will be some interactive process now. Thank goodness for that.

— Adrian Segar (@ASegar) September 7, 2022

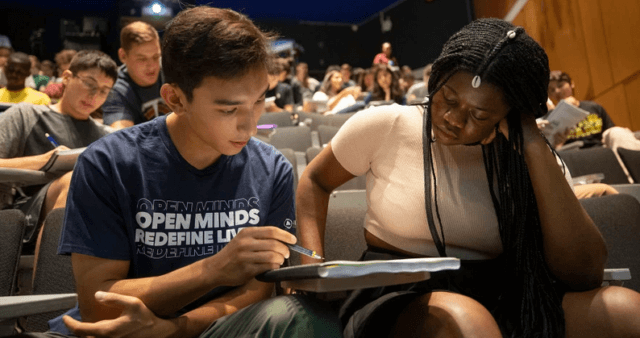

The book authors and webinar presenters Christina Katopodis and Cathy N. Davidson began well with the classic participative active learning exercise (think-)pair-share. This was fine for the in-person audience but not made available to the online audience. You can easily run pair (or preferably trio) share in small Zoom meetings using (up to 50) breakouts, but Zoom webinars don’t include this functionality. Still, even an online poll provides some activity for remote audiences.

I always found it difficult to get participants’ attention when closing a pair share, and this happened during the webinar too. As the presenters noted, that’s a good thing! For the in-person audience, this was the moment when they were most engaged during the entire session.

But, inadequate regular interactive processes followed

Unfortunately, subsequent interactive components were sorely lacking. National Teacher of the Year Professor John Medina, whom I interviewed in front of a live audience in 2015, and Professor Donald Bligh, author of What’s The Use Of Lectures?, both explain how presenters need to change their presentation process every ten minutes or less before attention flags.

At the 70-minute mark, I tweeted:

Need more interaction by this point of the #newcollegeclassroom webinar. Brains are turning off. 70 minutes have passed and we’ve had ONE interactive exercise. Rule of thumb is every ten minutes or less if you want to maintain active learning.

— Adrian Segar (@ASegar) September 7, 2022

The subsequent webinar content was good, but there was only one more interactive exercise (a poll about what people disliked about teaching). Christina and Cathy switched often—a good thing to do—and told a few stories during the remainder of the webinar. But the rest of the webinar used a lecture format.

And the seminar ended really early for the online audience!

To my surprise, the “presentation” portion of the putative two-hour session ended twenty minutes early, after the presenters had answered some audience questions. The in-person audience could get up and chat with each other, get copies of their books signed, etc. The online audience (the vast majority of those attending) had nothing to do!

The online audience, who had scheduled two hours out of their day to attend the seminar, only received seventy minutes of (potentially) useful content!

This was really unfortunate. I can think of a number of ways that the online audience could have been part of an active learning experience. Instead, I and the other 800 online attendees were dismissed from class early.

This experience indicates to me that the presenters hadn’t thought enough about the online audience’s experience. You need to put yourself in the place of an online attendee and design an experience that is as good for them as possible, rather than relegating them to second-class status. Especially when they comprise the vast majority of your audience!

Content notes

Opening pair share

The presenters started with a pair share on what people liked most about teaching. In-person participants did a pair share, while the online audience took a poll. A majority of the latter said they liked hearing what students had to say and helping them with life skills.

From English research: college teachers talk 87% of the time even in seminar classes.

One of the presenters uses pair share to start every class (as do I).

The presenters summarized the value of active learning. Pair share allows every student to contribute, by sharing their ideas with another student. “You have energy, and you have engagement and involvement, and you have commitment and participation. We know and have metrics on all of this. You learn better. Retain better.”

Thoughts about teaching

They mentioned research that found 20% of students graduate from college without ever having spoken in class unless they were directly called on. “That is a tragedy.”

“Part of what we are doing in this book is finding methods to allow every student to contribute what they have to say. The fancy word for this is metacognition; you think about the course contact and why you are learning and how you are learning what you are doing and that is the lesson that lasts a lifetime.”

“What do our students need from our teaching?”

“We have this idea that higher education hasn’t changed since Socrates and Plato walked around the lyceum. Not true, we saw enormous changes two years ago. In 1 week 18 million students went online during the pandemic. It’s hard to remember we brought higher ed online in a matter of weeks. That was a tremendous accomplishment.”

Active learning

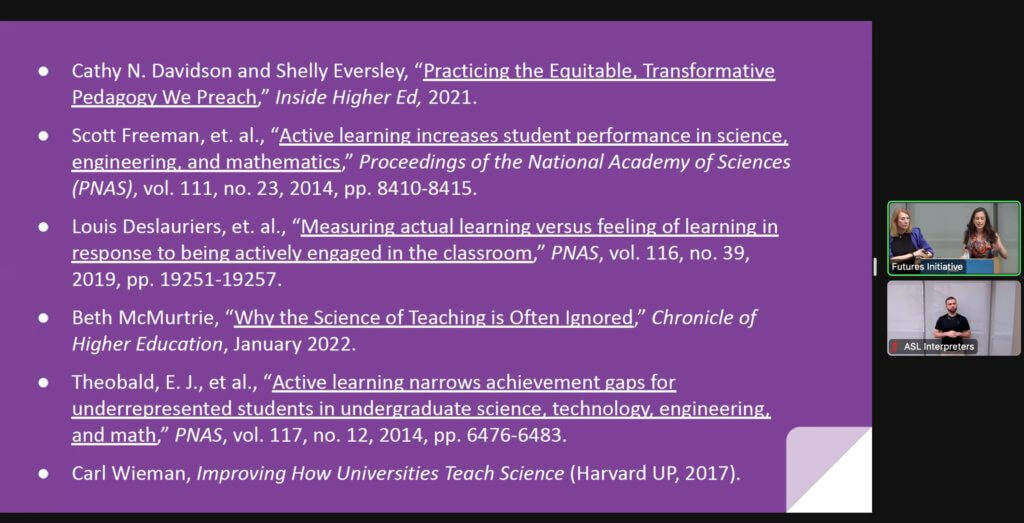

The presenters shared resources on the value of active learning. (There are more in my book, The Power of Participation.)

Answering questions

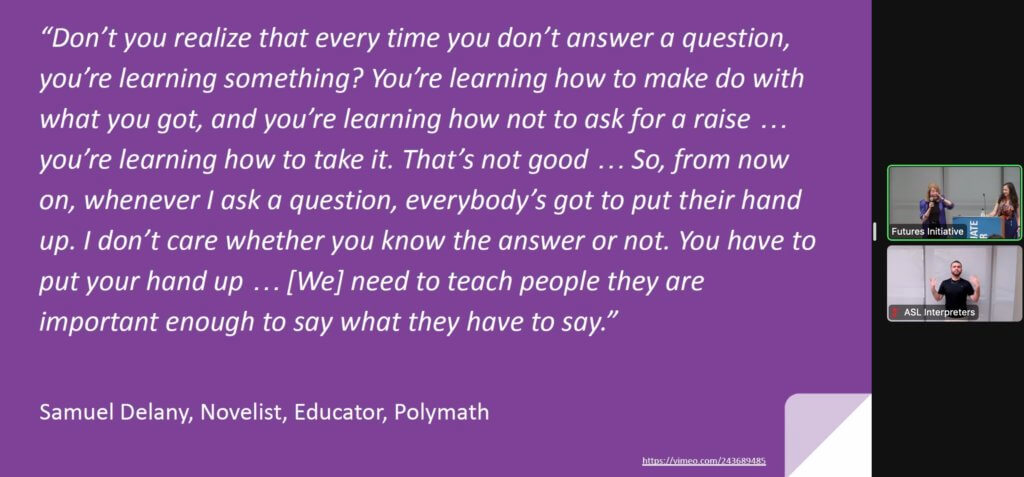

An interesting idea shared by science fiction writer and polymath Samuel Delany.

The Polymath, or the Life and Opinions of Samuel R. Delany, Gentleman from Fred Barney Taylor on Vimeo.

To which I responded…

Hadn’t heard the Samuel Delany quote before in the #newcollegeclassroom webinar. Like the approach, but it’s critical that participants are prepared so it’s safe — “‘I don’t know’ is an OK and common answer”.

— Adrian Segar (@ASegar) September 7, 2022

“On average, kids ask [around] twenty questions per hour. When they get to school, they ask three questions per hour. That is staggering. When they come to higher ed, there is all that unlearning that we have to do.”

Other session themes

As you’d expect, the presenters advocated using a flipped classroom model.

And they talked about:

- Starting a course by asking students how the course will change their life.

- The value of having students reflect on something they got wrong in class. “[Mistakes] shouldn’t be a source of shame.“

- Providing co-designed options for student assignments and evaluations.

- Having students write a question they want to ask toward the end of the class. (I prefer to do this at the start!)

I like to use a closing “exit ticket activity” pair share on lessons learned during the session.

The session closed with the presenters answering some questions about approaches to grading. (Grading was the least favorite aspect of teaching reported in the session’s second poll!) It’s a tricky topic, and I give thanks that I no longer teach college and have to deal with the difficult balancing act between my assessment of student learning and what organizations and society want to hear.

Kudos

This webinar did some things very well. Kudos for including ASL interpretation, real-time captioning, and a slightly delayed (but very usable), real-time, human-provided transcript.

Conclusion

A class is a meeting. This webinar was a meeting. It could have far more effectively demonstrated by example the power and value of the active learning that occurs with participant-driven and participation-rich education. The workshops I run put this into practice. Here’s an example. During them, I talk for less than ten minutes at a time.

Opening with formats like Post It! allows us to focus on what participants want to learn. Using fishbowl sandwiches for discussions ensures wide-ranging conversations. Many other formats are in my toolbox, ready to be pulled out and used when the need arises. I hope to see many of these valuable, tested approaches adopted widely by college teachers. Our students and our society will be better for it.

The meeting is over. Did anyone learn anything? And how would you know?

The meeting is over. Did anyone learn anything? And how would you know? In 2009, the biologist E.O. Wilson described what he saw as humanity’s real problem. I think it’s also a meeting problem:

In 2009, the biologist E.O. Wilson described what he saw as humanity’s real problem. I think it’s also a meeting problem: One of the best and simplest ways to build active learning and connection into any meeting is to regularly use

One of the best and simplest ways to build active learning and connection into any meeting is to regularly use  Providing downtime during any meeting is

Providing downtime during any meeting is  A

A  Ah, the ubiquitous conference one-hour lecture. How do I hate thee? Let me count the ways. Actually, I don’t need to do that since Donald Bligh listed them all in his classic book

Ah, the ubiquitous conference one-hour lecture. How do I hate thee? Let me count the ways. Actually, I don’t need to do that since Donald Bligh listed them all in his classic book  When mistaken beliefs about methods and outcomes harden into dogma, harm follows. The professional meeting industry largely believes that:

When mistaken beliefs about methods and outcomes harden into dogma, harm follows. The professional meeting industry largely believes that: The Solution Room is rapidly becoming a popular meeting plenary. Invented at MPI’s 2011 European Meetings and Events Conference, the session fosters active meaningful connections between attendees, and provides peer support and solutions to the real professional challenges currently faced by participants.

The Solution Room is rapidly becoming a popular meeting plenary. Invented at MPI’s 2011 European Meetings and Events Conference, the session fosters active meaningful connections between attendees, and provides peer support and solutions to the real professional challenges currently faced by participants.