How to work with others to change our lives

How to work with others to change our lives

How to work with others to change our lives

I belong to a couple of small groups that have been meeting regularly for decades. The men’s group meets biweekly, while the consultants’ group meets monthly. I have been exploring and writing about facilitating change since the earliest days of this blog. So in 2021, I developed and facilitated for each group a process for working together to explore what we want to change, and then change our lives.

Each group spent several meetings working through this exercise.

What happened was valuable, so I’m sharing the process for you to use if it fits.

The process design outline

It’s important for the group’s members to receive instructions for the entire exercise well in advance of the first meeting, so they have time to think about their answers before we get together.

Exploring our past experiences of working on change in our lives

We begin with a short, three-question review of our past experiences working on change in our lives.

These questions give everyone the opportunity to review:

- the life changes they made or attempted to make in the past;

- the strategies they used; and

- what they learned in the process.

This supplies baseline information to the individuals and the group for what follows.

The questions cover what:

- we worked on.

- was tried that did and didn’t work.

- we learned from these experiences.

We each share short answers to these questions before continuing to the next stage of the process.

For the rest of the exercise, each group member gets as much time as they need.

Sharing what we would currently like to change in our lives

Next, we ask each person to share anything they would currently like to change in their life. This includes issues they may or may not be working on. Group members can ask for help to clarify what they want to change.

Exploring and discussing what we are currently working on to change our lives

Next, each person shares in detail which of the above issues they are currently working on, or want to work on, to change in their life. This can include describing their struggles and what they are learning, and also asking the group for advice and support.

Post-process review

Exploring long-term learning is important. So, after some time has elapsed, perhaps a few months, we run a post-exercise review of the outcomes for each person. This helps to uncover successes as well as difficulties that surfaced, and can also lead to additional appropriate group support and encouragement.

Here’s an example — what I shared and did

Things I’ve tried in the past to make changes in my life that didn’t work

- Trying to think my way into making changes w/o taking my feelings/body state into account

e.g. trying to lose weight by going on a diet. - Denial—doing nothing and hoping the change will happen.

What I’ve learned about successful ways to change my life

- Anything that improves my awareness of feeling or body state can be a precursor to change: e.g. mindful eating or emotional eating.

- Creating habits: e.g. brushing my teeth first thing in the morning; setting triggers (calendar reminders, timers for meditation or breaks).

- The habit of daily exercise and regular yoga improves awareness of my body state.

Three issues I worked on

- Tidying up and documenting my complicated life before I die.

- Meditating daily.

- Living more in gratitude; developing a daily practice.

My post-exercise three-month review

- I’m happy with the way I continue to work on the long-term project of tidying up my office, getting caught up on reading, and documenting my household and estate tasks. To help ensure that I work on it every day, I created a simple spreadsheet with columns for various short tasks that advanced my goals. Checking off time spent on one of these tasks each day shows me I’m making progress, and this feels good.

- I created a buddy system with another group member who wanted to meditate more. We send each other an email when we’ve meditated. This has greatly improved the likelihood I’ll meditate every day.

- After trying a simple daily gratitude practice, I decided to let it go for the time being until my daily meditation became a fully reliable habit. Sometimes, small steps are the best strategy!

Detailed instructions

Interested? OK! Here’s how to run this exercise.

First, explain the process and see if you get buy-in from the group about doing this work. It’s helpful to explain that each person can choose what personal change they want to work on. There are no “right” or “wrong”, or “small” or “large” personal change issues. Any issue that someone wants to work on is valuable to that person, and that’s all that counts.

I think it’s helpful for everyone present to participate, rather than some people being observers, but ultimately, that’s up to the group to decide.

Well before the first meeting, share the following, adapted to your needs, with group members.

Working together to change our lives – the first meeting

“We’ve decided to work together on what we are currently trying to change in our lives. As we will have about an hour for this work at each session, we’ll need two or more meetings for everyone to have their turn.

For the exercise to be fruitful, we will all need to do some preparatory work before the meetings.

Our eventual focus will be on what we are currently trying to change in our lives, and how we are going about it.

We’ll start with questions 1) and 2) below, which are about the past. Please come with short (maximum 2½ minutes total per person) answers to them. Please answer question 3) in 90 seconds or less. At subsequent meetings, we will spend much more time on questions 4) & 5).

Please come to the first meeting prepared to answer the following three questions:

==> 1) What have you tried to make changes in your life that didn’t work? What have you learned over the last 20 years?

==> 2) What have you learned about successful ways to change your life over the last 20 years?

Don’t include childhood/teen lessons learned, unless you really think they’re still relevant to today’s work.

Remember: a maximum of 2½ minutes for questions 1) and 2) combined!

==> 3) What would you currently like to change about how you live your life? (You might not be working on it. You can ask for advice if you want.)

Be as specific as possible in your answer to question 3). Your answer should take 90 seconds or less! (But we’ll provide more time if you want or need help clarifying your goals.)

Working together to change our lives – subsequent meetings

At subsequent meetings, we’ll each take turns to answer questions 4) and 5) below. You’ll have as much time as you need to answer these questions and partake in the subsequent discussion.

==> 4) What are you currently working on to change in your life?

==> 5) How are you going about making the changes you shared in your answer to question 4)? What are the struggles and what are you learning? What advice would you like?”

Running the meetings

At the first meeting, you’ll typically have time for everyone to share their answers to the first three questions. Keep track of the time, be flexible, but don’t let participants ramble. It’s very helpful for the facilitator to take brief notes on what people share. If there’s still time available, I suggest you/the facilitator model the process by sharing their answers to questions 4) and 5) and holding an appropriate discussion. Use subsequent meetings as needed for every group member in turn to answer and discuss these two final questions, and write notes on these discussions too.

The post-exercise review

When this exercise has been completed for everyone, I suggest the group schedule a follow-up review in a few months. If your group starts with check-ins, it can be useful to regularly remind everyone about the review and ask if anything’s come up that someone would like to discuss before the review meeting.

Before the post-exercise review, let group members know that the facilitator will share their notes for each person in turn, and ask them to comment on what’s happened since.

At the start of the post-exercise review, explain that this is an opportunity to share information — discoveries, roadblocks, successes, etc. — without judgment. It’s also a time when group members can ask for ideas, advice, and support from each other.

Finally, you may decide to return to this exercise at a later date. After all, there’s much to be said for working on change throughout our lives. The above process may be the same, but the answers the next time may be quite different!

Have you tried this exercise? How did it work for you? Did you change/improve it in some way? I’d love to hear about your experience with it — please share in the comments below!

How to work with others to change our lives

How to work with others to change our lives

It’s tempting and understandable to concentrate on trying to manage change. After all, we are constantly experiencing change, and attempting to manage it is often unavoidable. But never lose sight of the importance of working on what to change. As Seth Godin reminds us:

It’s tempting and understandable to concentrate on trying to manage change. After all, we are constantly experiencing change, and attempting to manage it is often unavoidable. But never lose sight of the importance of working on what to change. As Seth Godin reminds us:

Right now I’m living at home, and the two workouts I do most often are my daily outdoor run and yoga. So it’s convenient that these options are the first two I see.

Right now I’m living at home, and the two workouts I do most often are my daily outdoor run and yoga. So it’s convenient that these options are the first two I see. How can we work on facilitating change in our lives?

How can we work on facilitating change in our lives?

How can we successfully work with others for change and action?

How can we successfully work with others for change and action? Watch out for folks who are quick to share opinions about what should be done, but always leave the work they propose to others.

Watch out for folks who are quick to share opinions about what should be done, but always leave the work they propose to others.

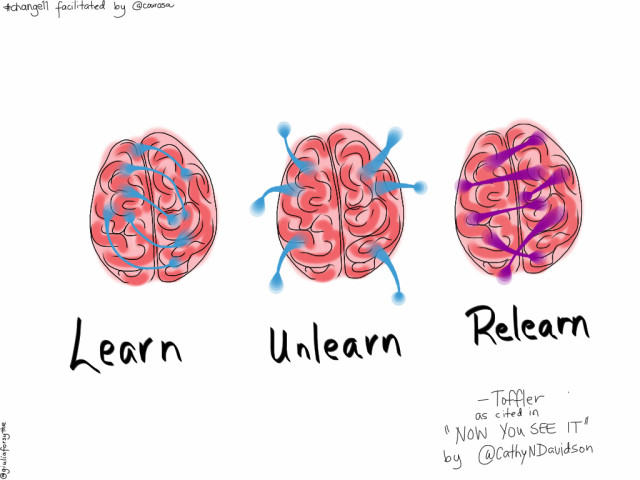

Unlearning is crucial for change.

Unlearning is crucial for change.![The first hill is the hardest: a photograph of a man running on a flat country dirt road. Photo attribution: Jenny Hill jennyhill [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.conferencesthatwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Runner_in_Stainburn_Forest-640x426.jpg)

I still remember the day, several months after I started, when I ran the whole route.

I still remember the day, several months after I started, when I ran the whole route. “Contains active cultures.” How often have you read this on the sides of yogurt containers? Well, healthy organizations contain active cultures too.

“Contains active cultures.” How often have you read this on the sides of yogurt containers? Well, healthy organizations contain active cultures too.